The asteroid that extinguished the dinosaurs is estimated to have been about 10 kilometers across. That’s about as wide as Brooklyn, New York. Such a massive impactor is predicted to hit Earth rarely, once every 100 million to 500 million years.

In contrast, much smaller asteroids, about the size of a bus, can strike Earth more frequently, every few years. These “decameter” asteroids, measuring just tens of meters across, are more likely to escape the main asteroid belt and migrate in to become near-Earth objects. If they make impact, these small but mighty space rocks can send shockwaves through entire regions, such as the 1908 impact in Tunguska, Siberia, and the 2013 asteroid that broke up in the sky over Chelyabinsk, Urals. Being able to observe decameter main-belt asteroids would provide a window into the origin of meteorites.

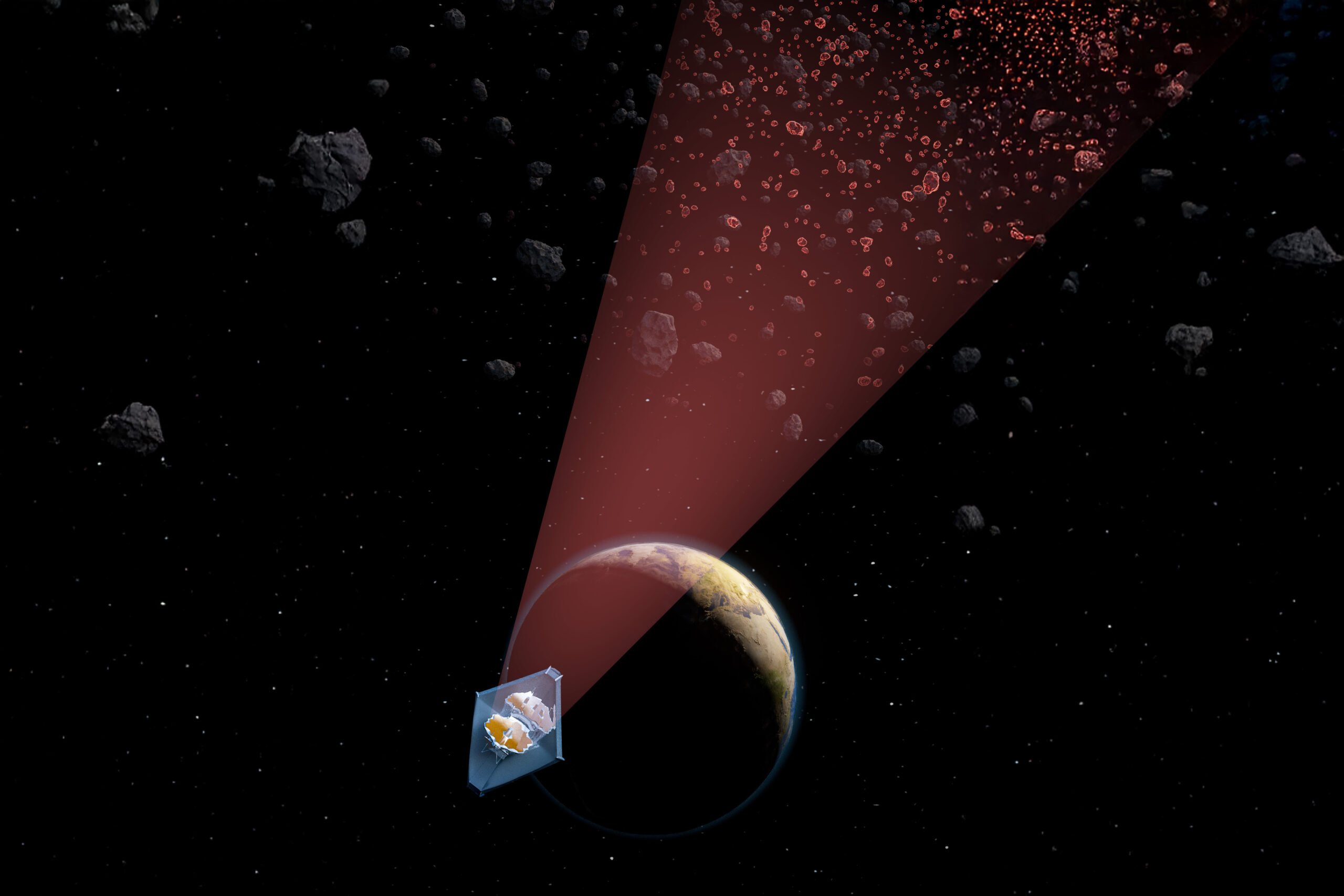

Now, an international team led by physicists at MIT have found a way to spot the smallest decameter asteroids within the main asteroid belt — a rubble field between Mars and Jupiter where millions of asteroids orbit. Until now, the smallest asteroids that scientists were able to discern there were about a kilometer in diameter. With the team’s new approach, scientists can now spot asteroids in the main belt as small as 10 meters across.

In a paper appearing today in the journal Nature, the researchers report that they have used their approach to detect more than 100 new decameter asteroids in the main asteroid belt. The space rocks range from the size of a bus to several stadiums wide, and are the smallest asteroids within the main belt that have been detected to date.

initially tried their approach on data from the SPECULOOS (Search for habitable Planets EClipsing ULtra-cOOl Stars) survey — a system of ground-based telescopes that takes many images of a star over time. This effort, along with a second application using data from a telescope in Antarctica, showed that researchers could indeed spot a vast amount of new asteroids in the main belt.

initially tried their approach on data from the SPECULOOS (Search for habitable Planets EClipsing ULtra-cOOl Stars) survey — a system of ground-based telescopes that takes many images of a star over time. This effort, along with a second application using data from a telescope in Antarctica, showed that researchers could indeed spot a vast amount of new asteroids in the main belt.

“An unexplored space”

For the new study, the researchers looked for more asteroids, down to smaller sizes, using data from the world’s most powerful observatory — NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), which is particularly sensitive to infrared rather than visible light. As it happens, asteroids that orbit in the main asteroid belt are much brighter at infrared wavelengths than at visible wavelengths, and thus are far easier to detect with JWST’s infrared capabilities.

The team applied their approach to JWST images of TRAPPIST-1. The data comprised more than 10,000 images of the star, which were originally obtained to search for signs of atmospheres around the system’s inner planets. After processing the images, the researchers were able to spot eight known asteroids in the main belt. They then looked further and discovered 138 new asteroids around the main belt, all within tens of meters in diameter — the smallest main belt asteroids detected to date. They suspect a few asteroids are on their way to becoming near-Earth objects, while one is likely a Trojan — an asteroid that trails Jupiter.

“We thought we would just detect a few new objects, but we detected so many more than expected, especially small ones,” de Wit says. “It is a sign that we are probing a new population regime, where many more small objects are formed through cascades of collisions that are very efficient at breaking down asteroids below roughly 100 meters.”

“Statistics of these decameter main belt asteroids are critical for modelling,” adds Miroslav Broz, co-author from the Prague Charles University in Czech Republic, and a specialist of the various asteroid populations in the solar system. “In fact, this is the debris ejected during collisions of bigger, kilometers-sized asteroids, which are observable and often exhibit similar orbits about the Sun, so that we group them into ‘families’ of asteroids.”

“This is a totally new, unexplored space we are entering, thanks to modern technologies,” Burdanov says. “It’s a good example of what we can do as a field when we look at the data differently. Sometimes there’s a big payoff, and this is one of them.”

This work was supported, in part, by the Heising-Simons Foundation, the Czech Science Foundation, and the NVIDIA Academic Hardware Grant Program.

Leave a Reply